Kansas restarts the Kansas City Border War in attempt to poach the Chiefs from Missouri

When a pro sports team packs up and moves to a new state, it can deal a crushing blow to fans. When that new state ends up being just a few minutes away in the exact same metropolitan area, that blow might reopen decades-old wounds.

That’s what could happen with Super Bowl champion the Kansas City Chiefs, once their current lease on a sports complex shared with the MLB’s Kansas City Royals expires in 2031. In April, Missouri voters said “no thanks” to a tax measure that would’ve helped fund a new $2 billion stadium for the Royals and an $800 million overhaul of the Chiefs’ Arrowhead Stadium. Then, Kansas moved in.

This week, Kansas lawmakers approved a tax-incentive bill that would allow the state to issue bonds covering up to 70% of the estimated $3.5 billion cost of two brand-new stadiums for the teams. Kansas would pay off the bonds over 30 years with money made from sports betting and the state lottery. Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly is expected to approve the proposal, which experts have called a “blank check” for the Chiefs.

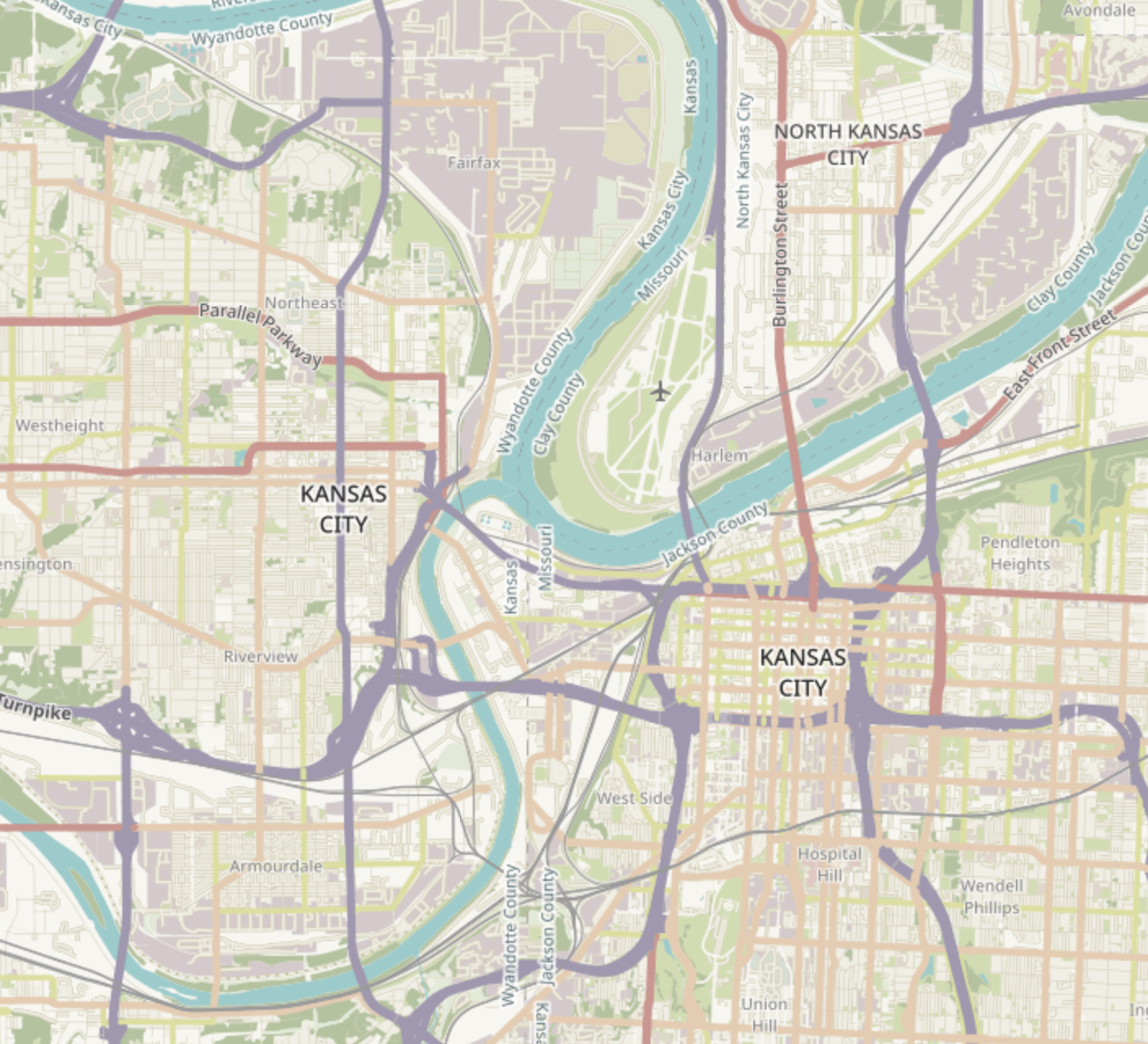

For the Chiefs and Royals, moving would mean packing up their current stadiums in Kansas City, Missouri (population 509,000), and taking a short drive across state lines to their hypothetical new stadiums in Kansas City, Kansas (population 157,000).

A brief history of the Kansas City Border War

It might seem odd for neighboring states that share a metro area (and labor market) to compete for pro sports teams, but it’s far from the first time the states have feuded over business in the area. A “border war” went on for many years, with each spending millions of dollars in taxpayer money to tempt businesses from one side to the other. Companies like AMC Theatres and Applebee’s crossed state lines to claim subsidies, sometimes multiple times, before the two states finally reached a legally binding truce five years ago.

In the decade leading up to the truce, Kansas and Missouri spent an estimated $335 million luring companies from state to state. In the end, Kansas came out slightly on top with roughly 1,200 jobs.

“It was really, truly these companies moving a couple miles down the road and literally nothing changing,” said Pat Garofalo, director of state and local policy at the American Economic Liberties Project and author of “The Billionaire Boondoggle.” “Like, people had to alter their commutes a little bit.”

Whether the brazen attempt by Kansas to draw one of Missouri’s primary attractions over to its side of the river will reignite the border war is yet to be seen. Some Missouri lawmakers already see the tax-incentive bill as a violation of the truce, but Gov. Kelly has said the agreement was about businesses and not teams.

The Chiefs players would probably be happy with a change: the team's facilities and ownership got abysmal ratings on the NFL Players Association player survey this year. Wherever the KC teams end up, Garofalo says it won’t be all that clear which state actually “won" (though he added that Missouri-based fans might get a W just by being off the hook for a giant subsidy package).

A hard-won truce, thrown away for little gain

“There’s really no reason to think that this will be economically beneficial,” Garofalo said.

“The job creation is almost always zero in these instances anyway, and the jobs that are created are bad, because we’re talking about seasonal, no-benefit, you know, rocking-popcorn-in-the-stands-type gigs.”

Studies have long shown that subsidies for sports stadiums don’t pay off.

The MLB’s Atlanta Braves relocated from downtown Atlanta to a suburb 10 miles north in 2017, and economist J.C. Bradbury found that the deal is costing taxpayers about $15 million/year. In New York, a near $1.7 billion new stadium for the Buffalo Bills will cost taxpayers $850 million. A preliminary economic analysis of the stadium found that the largest fiscal revenue source the state gains from the deal comes from personal income taxes paid by the team’s players.

Garofalo notes that it’s not often economists agree on, well, anything. For stadium subsidies, though, that’s not the case.

“The evidence is just overwhelming. There’s no question anymore amongst the people who look at this on the data and academic side,” he said.

“Publicly funded sports stadiums do not provide economic benefits. Like, period, full stop, we’re done, no question about it.”