The economics of Netflix aren’t what they used to be... they’re a lot better

Price rises and a crackdown on password sharing haven’t been popular with users, but shareholders are loving it

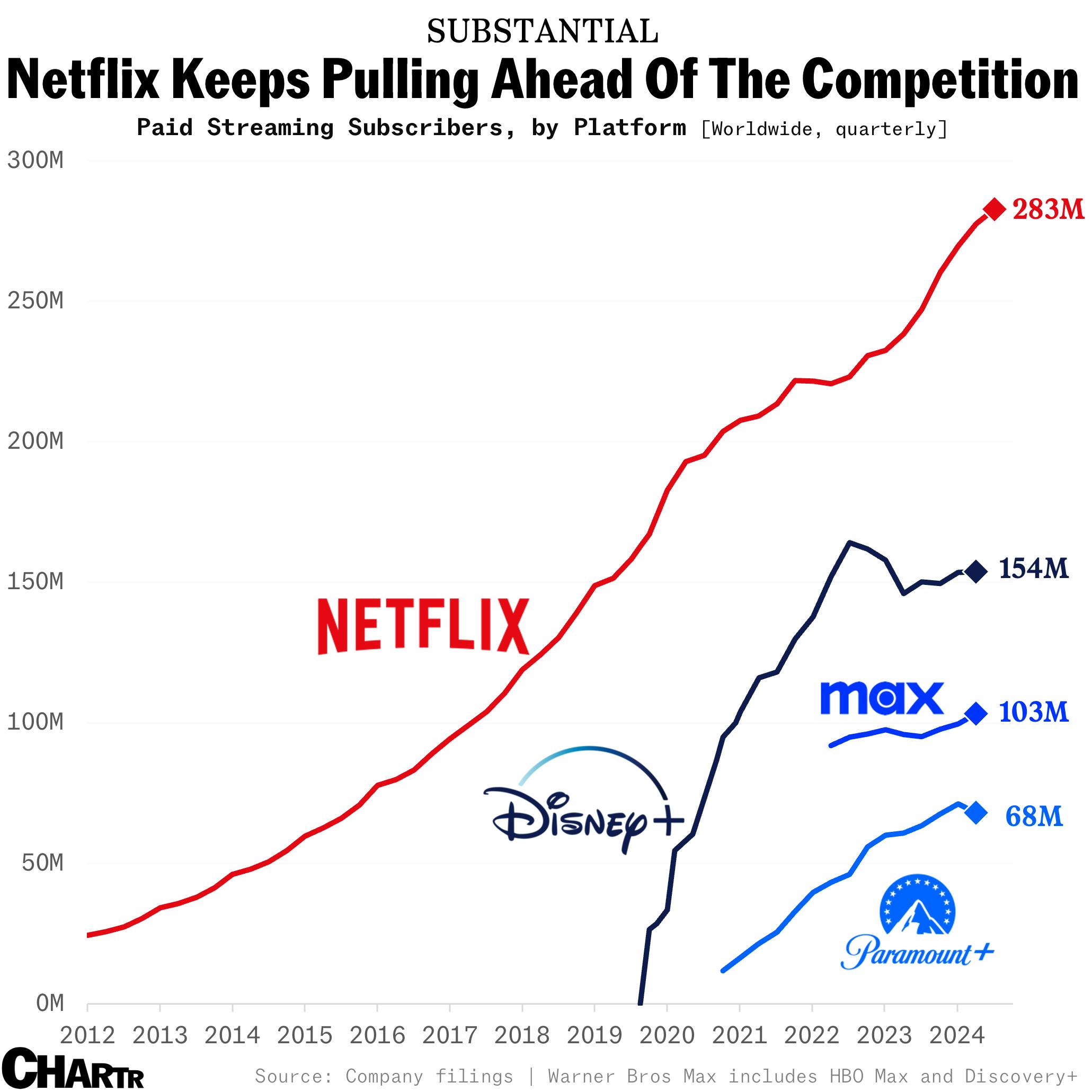

Yesterday Netflix rubber-stamped an idea that began as a whisper last year and has slowly become more evident with every passing quarter: the streaming wars are over, and Reed Hastings’ company came out on top.

Going against the grain of what some of us might feel — which is that we’re just one night of frustrated Netflix scrolling away from canceling the service after its price rises and password-sharing crackdown — the company’s latest earnings reveal that it’s healthier than ever. Netflix, which started life in 1997 as a mail-only DVD service, reported another quarter of subscriber gains, taking its global total to almost 283 million, with user numbers in all four of the company’s major regions growing in the last 12 months. In countries where it is available, more than 50% of signups in the third quarter were for the company’s cheaper ad-supported tier.

That result takes Netflix further ahead of its chief rivals, like Disney+, counting roughly 130 million more subscribers than its closest competition. Indeed, as we noted recently, Netflix’s real competition might actually be YouTube. In the six months leading up to July, 25% of all time spent streaming on US televisions was on YouTube, compared to ~20% on Netflix, according to data from Nielsen via Variety.

With the most expensive Netflix package now costing $22.99 per month in the US, the company’s business model — which requires spending tens of billions of dollars on content every year — is starting to show the benefits of its scale. It turns out that raising prices, while still growing your customer base, is an unsurprising recipe for success: Netflix’s third quarter was the company’s most profitable in its history, with profits up 41% year on year.

So how is Netflix pulling away from its competition? One factor that’s hard to ignore is that Netflix has simply been in this game — the business of showing you stuff to watch over the internet — longer than anyone else. The company doesn’t have a huge box office business, or theme parks, or an aging cable-TV network to distract it. What they do have is data. In fact, Netflix has more detailed data on what audiences enjoy, what they actually watch and not just what they say they watch, than any organization has ever had. They have data on which parts of the show people skip, which thumbnail is most likely to get clicked on, whether people revisit shows and watch them time and time again, what shows are working better in other regions — and what might be ripe to be plucked from their regional market to go global (think “Squid Game”).

I watched “The Night Agent,” a Netflix spy thriller, last year. I don’t think I’ve recommended it to a single friend to watch. It was completely fine. But for all of its OK-ness, something about it kept me coming back to watch another episode, and I stuck through the whole thing. I wasn’t alone. In fact, “The Night Agent” was Netflix’s most-watched show last year, racking up more than 812 million hours of viewing time. Taking a risk and spending millions of dollars on a show or movie, knowing that it could potentially be a hit like “The Night Agent,” gets easier with each passing quarter for Netflix, as it spreads its enormous content bill across more and more subscribers.

Take the company’s latest earnings as an example to illustrate just where Netflix’s money goes.

With 282.7 million subscribers, we can work out that the average Netflix subscriber was worth $11.60 per month to the company in Q3.

The vast majority of that will be subscription revenue. Some will be from advertising, but the company doesn’t disclose how much yet. So, using our $11.60 figure as our starting point, what does that monthly subscription get spent on?

A little more than six bucks, or just over half, gets spent on delivering the actual content. That’s the cost of licenses, production, and content delivery. Marketing takes another $0.76, technology and development costs $0.87, and general overheads cost almost $0.50, too. So out of your $11.60 monthly subscription, Netflix is left with a pretty tidy $3.44 in operating profit, which after interest expenses and taxes gets whittled down to $2.79, a still healthy 24% profit margin.

The long-term question is: for how much longer can Netflix keep raising prices? That practice is similar to boiling consumers like frogs, going unnoticed until one day you say, “Hey, this service that used to cost $10 a month is now rapidly approaching the cost of cable TV.”

Interestingly, the company plans to stop disclosing its all-important subscriber numbers next year. Usually, companies deciding to be less transparent is poorly received by investors, but when the profits keep stacking up, it seems you get a pass. Netflix is now worth $324 billion, that’s 85% more than Disney ($175 billion).