Big Tech is back to doing what it does best: gobbling up startups for billions

Google inked its biggest deal ever, Nvidia reportedly bought Gretel, and Meta is chasing an AI chip startup — and that was just in the last week. The flurry of dealmaking could continue.

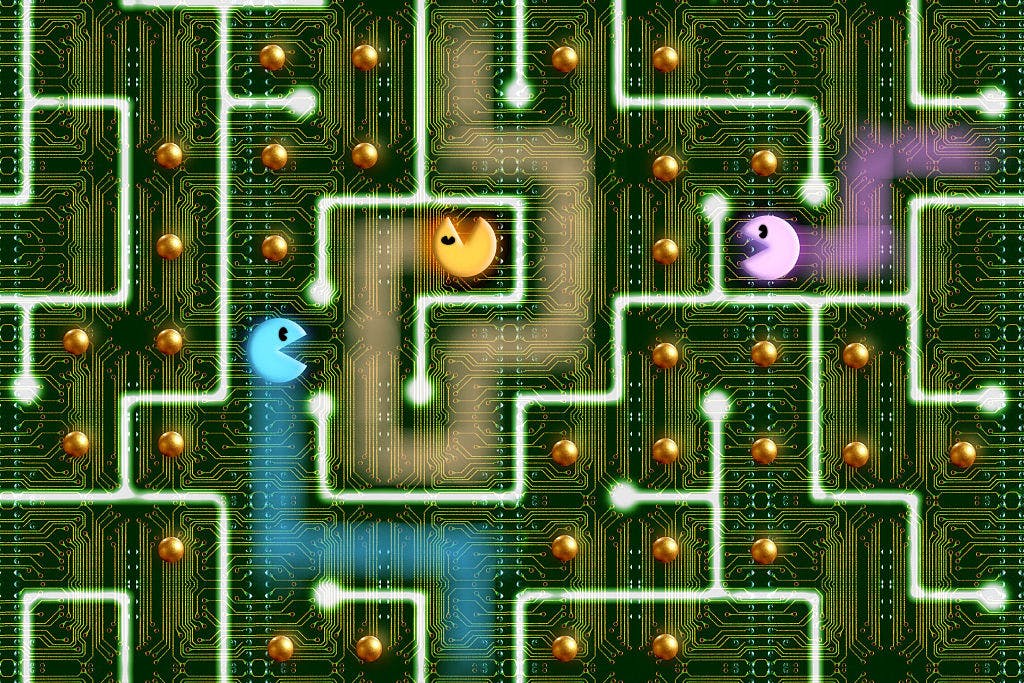

The technology world is Pac-Man. Big Tech navigates a maze of hardware, software, and talent, trying to build products that change the world, or just make a lot of money, while avoiding the ghosts — regulation, product obsolescence, or consumer backlash — that could take them down.

Along the way they swallow a lot of startups, little pills and pockets of growth that could become a core offering of their platform, like Meta’s 2012 deal for Instagram, or Google’s YouTube tie-up from 2006.

And in 2025, with AI shaking the foundations of almost every tech-adjacent vertical and a new administration in the White House that might be more acquisition-friendly, the giants are keen to strike some deals.

Just last week, Google finally clinched its deal for Wiz. After its $23 billion approach was rebuffed in July of last year, Google gave the cybersecurity startup an additional 9 billion reasons to say yes, agreeing to a $32 billion takeover with an eye-watering 10% break fee, well above the 4% to 7% typically seen in tech mergers and acquisitions. That $3.2 billion gamble is an indication of two things: Google really wanted this one, and it doesn’t see much of a risk of things blowing up after the agreement was signed. Simultaneously, Meta is reportedly after FuriosaAI, a Korean startup with expertise in AI hardware infrastructure, but its $800 million offer was rejected, according to Bloomberg reporting on Monday.

But it’s not just Meta and Google looking for deals, with data compiled by CB Insights revealing that 11 venture-backed startups were acquired for more than $1 billion in Q1 2025, for a total value of $54.5 billion — the largest quarterly sum on record, driven by Google’s Wiz deal. For comparison, last year, only two startups were bought for more than $1 billion.

There are good reasons to expect that this flurry of acquisitions could continue into the future. For starters, the regulatory environment is now wildly different. Lina Khan, who rose to prominence after publishing a prescient article titled “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox,” is out as chair of the Federal Trade Commission. Her successor, Andrew Ferguson, is likely to take a lighter touch to scrutinizing dealmaking. Speaking to CNBC on March 13, Ferguson had this to say about the FTC’s approach to M&A (emphasis ours):

“Here’s what I want to say about that — if we’ve got a merger or conduct that violates the antitrust laws, and I think I can prove it in court, I’m going to take you to court. And if we don’t, I’m going to get the hell out of the way. The FTC is not going to try to use sort of sub-regulatory means to hold up mergers without actually taking people to court and hope that they die on the vine. That’s over. If we think it violates the laws, we’re going to litigate. And if it doesn’t, we’re going to get out of the way and we’re going to let markets do their thing.”

Sellers might also be more willing to transact than they were previously. Speaking to Bloomberg, David Chen, head of global technology investment banking at Morgan Stanley, said, “The sellers’ willingness to transact has actually improved,” in part due to volatility in markets. Though stocks have bounced slightly this week, fears of a recession and the potential of an accompanying bear market may make a nice soft landing into the arms of a corporate giant a more appealing prospect for founders and leaders of high-flying startups who have a lot of wealth on paper that they’d like to finally cash in. Even “fearless founders” get spooked.

Build or buy?

For would-be corporate acquirers, the AI boom presents a ripe environment for acquisitions, but with every potential deal, the team has to make an evaluation: do we try and build this ourselves, or just go out and buy it?

If a startup has something you want — maybe a product, a piece of technology, or just a rockstar team — an acquisition trades time for money.

Given the speed of change in the field of AI, the tech giants, who are already on track to spend an eye-watering $315 billion on capital expenditures this year, might be willing to spend a little bit more to acquire the tools and talent they need to compete. It’s not the time to keep your powder dry in the hope of saving a few bucks.

Just a week ago, Nvidia reportedly bought Gretel, a synthetic data startup that, according to its website, can help you “generate artificial, synthetic datasets with the same characteristics as real data, so you can improve AI models without compromising on privacy.” Exact terms of the deal weren’t disclosed, but it was said to be in excess of Gretel’s most recent $320 million valuation. That’s a drop in the ocean for Nvidia, but it’s a telling maneuver nonetheless, because Nvidia has typically been one of the least acquisitive of its peers.

According to data from Crunchbase, Nvidia has acquired just 30 companies. Google, through owner and parent company Alphabet, has bought 267, ahead of the next most acquisitive tech company, Microsoft, which has acquired 256 companies.

With investors falling over themselves to bid up the equity of companies that show the most progress on AI, it seems logical to assume that deals will follow, and with the balance sheets of Big Tech as healthy as they’ve ever been, the financial firepower is certainly there. Policy uncertainty — which has soared this year — could thwart that thesis.

What would have become of all of these startups gobbled up by Big Tech? As my colleague Matt Phillips and I wrote last year, many of them might have become public companies, meaningful competitors... or both.

Go Deeper: Where did all the stocks go?